SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY

“All our lauded technological progress—our very civilization—is like the axe in the hand of the pathological criminal.”

~Albert Einstein

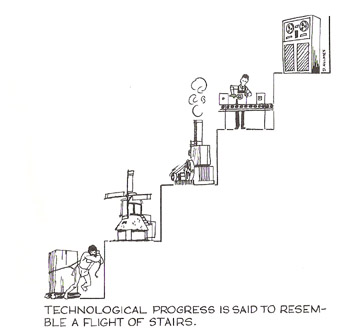

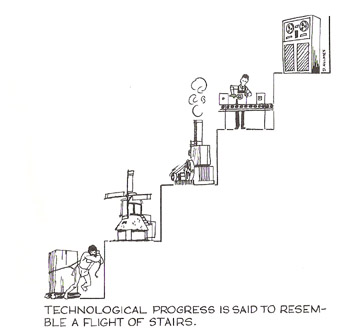

Graphic from a US Federal Reserve pamphlet c.1960

“All our lauded technological progress—our very civilization—is like the axe in the hand of the pathological criminal.”

~Albert Einstein

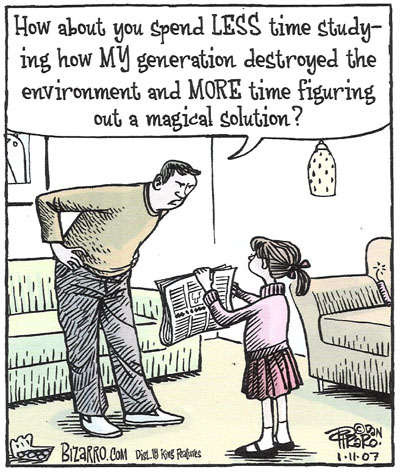

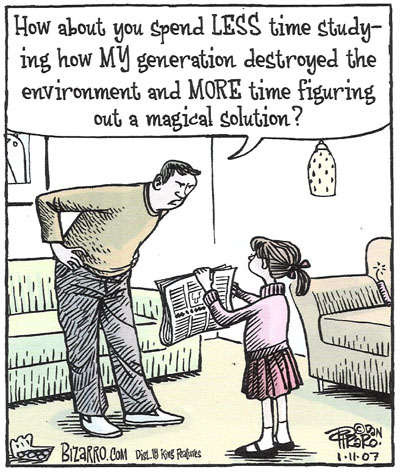

Almost all of today’s problems are caused by yesterday’s technological solutions to problems of the day. Civilization’s stairway of Babel, shown above, has a down side each step of the way.

For example, Electric cars.

Mapping known asteroids’ paths is underway, with an increasing number of Near Earth Objects (NEOs) and Near Earth Asteroids (NEAs) projected into the future and deemed clear of Earth’s path. A lack of funding keeps this from progressing as it could, since it doesn’t relate to power by one group of people over another, nor are profits likely within the next quarter, if ever.

Meanwhile, militarization of space, despite treaties to the contrary, marches onward and upward through efforts of the US government. This “Star wars” project isn’t to protect Earth from extraterrestrial threats, it’s to dominate the world. China has recently joined the potential arms race in space. Once again, rather than being the best hope against global threats, humans are the greatest threat. In fact, we aren’t just a threat: unlike that random uncharted asteroid floating around out there somewhere, we’re actively causing deep impacts on planet Earth.

Comets would be a bigger challenge than asteroids: we only learn about new ones after it’s too late to do much about them with our current technology. If we are to develop the means to deflect extra-terrestrial threats, priorities will have to change. This could be done more easily with fewer of us. If we can’t get the job done with six billion, we sure aren’t going to do it with nine. Trying to keep up with our growing demands for resources prevents us from making real progress.

There are threats to life on Earth which we have no power to stop. A supervolcano blew in 535 near the island of Java and obscured the Sun for a year. Effects were global and long-lasting, both on humans and the natural world. There are at least seven more of these around the planet, including Yellowstone, which could do the same. There’s nothing we can do to control forces like these.

We do have the power to eliminate one clear and present danger to Earth’s biosphere: our own excessive presence. Our voluntary extinction could mercifully prevent a major ecological collapse, if we act soon enough.

Near Earth Object dynamic

site tracks nearly 6,000 bodies.

Apophis asteroid possible impact

in 2036.

Q: Why not clone extinct species from their DNA codes?

Jurassic Park is a movie—it’s not possible in real life.

But, just for fun, let’s bring back the Tasmanian tiger, or Tasmanian

wolf if you prefer—real name thylacine (THIGH-luh-sign). Last known

survivor, shown here, died in Hobart Zoo in 1936.

A baby specimen was preserved in alcohol in 1866, rather than DNA-destroying

formalin, and rests on a shelf in the Australian Museum. Offering the

pickled, pouched mammal for research, director Mike Archer, envisions

thylacines as pets within 50 years.

First, the DNA has to be decoded. No problem, with a big enough grant, but that’s as far as we’ll get.

Enough species which used to live in and on the thylacine must also be recreated from their DNA. Being microscopic and extinct is a good way to keep from being found and decoded. Some species of bacteria, which are similar enough to get the thylacine’s food digested, might exist in another carnivorous marsupial—now where did they all get to?

Which brings up another obstacle: who’s the mommy? When daddy Frankenstein breathes life into the accurately-DNA-encoded glob of inert ingredients, it then has to grow inside an adult. In this case, one with a nice warm pouch is preferred. Maybe a kangaroo will do, if our tiger cub doesn’t bite too much.

So, assuming we’ve overcome those little details: got 10 or 20 micro organisms recreated and kicking, found a way to create life from lifeless matter, and found a surrogate mom—where will it call home?

Habitat loss causes most extinctions today. Ranchers converted thylacine habitat into rangeland for livestock. When Tasmanian Tigers had the gall to dine on the exotic lamb delivered to their homes, they were shot as pests—bounties paid. Unless large expanses of rangeland are restored as natural habitat—another monumental challenge for science and politics—they would still be considered pests.

Livestock interests continue blocking efforts to reintroduce wolves,

grizzlies, and bison in western North America. Considerable ground for

wildlife could be gained if we pulled the subsidies feed bag from grazers, and stopped buying their meat and by-products, but until we restore habitat on a large scale, even wildlife that doesn’t have to be brought back from

the dead has no home.

Hundreds

of wolves killed for livestock attacks

Government wolf kills increasing

Frozen Ark Project DNA of endangered species preserved for possible cloning.

Plan to recreate 88% mammoth from sperm DNA

Attempts to clone extinct Ibex

Q: Why not move excess human population to colonies on other planets?

That’s humanity for you: our sights are on the stars while we’re sinking in toxic sludge. For space migration to keep our numbers stable, 100 space ships holding 2,000 people each would have to blast off every day: one every 15 minutes. Contraception is cheaper.

New world colonization by Europeans didn’t relieve population pressure in Europe—just increased it elsewhere.

What kind of life would we primates, barely out of the jungle, make for ourselves in a space station? We aren’t domesticated enough to keep from going bonkers in remote, desolate outposts like Antarctica. Anyway, who wants to live inside a building for 10 or 20 years? To seriously imagine ourselves living that way reveals the extent of our mental disconnect from Nature.

We barely live healthy lives in our artificial environments here on Earth. Indoor air averages many times more toxic than outside air. Emotional stress resembles that of captive animals—for good reason. Although our cage bars may only be abstract, like the bars crossing the €, $, £, and ¥ in our money, their specter crosses our paths to freedom.

Dreaming of some day shooting our aspirations off into space could deaden our sense of responsibility here on Earth. We have a nasty habit of fouling our nests and moving on. The USA’s National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA) has jettisoned the phrase, “To understand and protect our home planet” from its mission statement. Already, near space is loaded with so much obsolete electronic junk and astronauts’ end products that NASA Space Shuttles and the International Space Station have to dodge or get a fatal hole. We’ve placed our cultural icons on the moon: a flag, a golf ball, and an abandoned vehicle.

Before we seek out new worlds and boldly go where no human has gone before, we have an obligation to clean up our messes on this world.

Let’s be grateful we don’t live on the moon or in space. Our personal castles on Earth may not be much, but our efforts often make them garden sanctuaries a thousand times nicer than luxury quarters in a giant tin can drifting in space.

Short simulation

video of space debris accumulation 1957-2000. (Not to scale)

More space junk information and A plan to tidy up near space

To join others who hope we can escape our involuntary extinction by fleeing the mess we’ve made of Earth: Spaceflight or Extinction and Reopening the Space Frontier.

For a comprehensive collection of quotes from those who believe humanity

should expand to other planets: Space

Quotes.

Q: If we spread life to other planets, wouldn’t there be more chance for it to survive?

At first, spreading life might sound like a noble idea. British explorer Captain Cook would offer Pacific islands chiefs a breeding pair of pigs, and was disgusted by the ignorance of some primitives who just slaughtered the gifts for a luau. Yum, European exotic invader. . . Cook, et all. Feral pigs are still negatively impacting ecosystems in Hawai’i and elsewhere.

Our experience here on Earth with exotic species devastating ecosystems should give adequate warning of the folly of introducing species to other seemingly-uninhabited planets. Take starlings and house sparrows... please. Folks who blessed North America with all the birds from Shakespeare’s works thought they were on a righteous mission—sort of like the fantasy of spreading Earth life all over the Universe might be.

It’s not impossible that someday we may be able to create conditions on some lifeless orbiting rock to support life as we imagine it could be. We could also find lifeless places right here and restore them to ecological integrity. Chernobyl, Hanford, and other death zones would be good starts. Perhaps before we figure on terra-forming elsewhere we ought to stop terra-deforming here.

Down-to-Earth solutions exist already—we only need to use them, coupled with improved birth rates on a global scale. Adjustments of our priorities could create a wonderful world for all life. It starts with each of us making responsible choices.